Weekly Issue

I have spent a lot of time talking about the difference between buying a story and buying a business. Deep value is the discipline of buying a business at a price that already bakes in a big margin of safety. If we get the math right at the start, we do not need to predict the future with a crystal ball. We need the price to be far less than conservatively appraised value and we need the balance sheet to let the business survive long enough for value to show up. That is the heart of this long form.

I have learned to build from Ben Graham’s foundations, bring in Marty Whitman’s credit and asset discipline, fuse the two into a modern playbook, and then go hunting in the U.S. and abroad where the discounts are widest today.

Section 1. Ben Graham’s approach, from classic deep value to simple, mechanical rules

Benjamin Graham built the bedrock of deep value investing during the 1930s after watching the market break itself. The core is simple. Buy securities at a large discount to intrinsic value. Insist on a real margin of safety at the moment of purchase.

Measure success by what the whole basket of bargains does over time, not by whether any one pick makes you look brilliant.

Graham’s famous net net method is the cleanest example of buying dollars for cents. Net current asset value is current assets minus all liabilities, with no credit given to plant or other fixed assets. If the stock price is less than that working capital number, you buy as part of a diversified basket.

Historically, this produced strong group results for Graham over about three decades. He described the approach as almost unfailingly dependable when the opportunities were available, and he attributed roughly 20 percent annual returns to this source during those years.

The power came from the group, not from predicting the fate of each individual company.

Late in life, Graham changed how he wanted investors to apply his ideas. In his final interview in 1976 he said the edge no longer came from ever more elaborate deep dive analysis because professional research had become ubiquitous.

His answer was to go the other way. Keep it simple.

Use very basic price-based rules that prove full value is present at the price you are paying. Rely on the portfolio’s group results rather than on brilliant forecasts.

He also pointed out that individuals have an advantage over institutions. Institutions are forced to crowd into a few hundred mega caps. Individuals can fish in thousands of neglected names and should be able at all times to locate around 30 attractive issues.

Graham laid down three policy rules.

Act like an investor, not a speculator. Every purchase must be justified by impersonal reasoning that value exceeds price. The margin of safety lives at the buy price.

Pre set the sell discipline. A reasonable gain objective is roughly 50% to 100% and a maximum holding period is about 2 to 3 years. If the gain does not arrive within that window, sell and recycle the capital.

Keep a balanced core and rebalance. Maintain at least 25% in stocks and 25% in bond equivalents at all times. A steady 50 to 50 split is fine for most investors. Trim stocks into strength and add on weakness. For bonds, an average maturity of about 7 to 8 years is sensible.

He also gave two simple, mechanical ways to build the stock sleeve.

A. The working capital or net net method. Buy stocks below net current asset value, ignoring fixed assets and deducting all liabilities. Use a basket. Let the group do the work. Historically this was a powerful source of returns for his funds.

B. The one or two criterion method that proves full value is present. Buy groups of stocks that are clearly cheap on extremely basic tests. Graham’s preferred screen was price to earnings less than or equal to 7 on last twelve months reported earnings.

He also cited a dividend yield of at least 7 percent or book value equal to at least 120 percent of the stock price, which corresponds to price to book of about 0.83.

Across 1925 to 1975 he said these mechanical group methods produced roughly 15 percent or better annualized returns, about double the Dow over that span.

Graham’s ideas did not stay in the classroom.

They minted fortunes.

Warren Buffett’s 1984 essay The Superinvestors of Graham and Doddsville documented multiple disciples who compounded at superior rates for decades by sticking to Graham’s rules in their own ways. Walter Schloss ran a simple cheap stock strategy and produced about 21 percent annual returns from 1956 to 1984 against roughly 8 percent for the market. Bill Ruane, Tom Knapp and Tweedy Browne, Irving Kahn, and others showed that disciplined buying of undervalued securities can beat broad indexes over very long horizons.

The message is not that you must be a genius. The message is that if you insist on a margin of safety up front and you let group results work, the math does the heavy lifting.

Section 2. Martin Whitman’s asset based, credit first value

Where Graham began with earnings power and working capital bargains,Marty Whitman put the balance sheet at the center of deep value. He built Third Avenue Management by thinking like an owner and a creditor at the same time.

The Whitman lens is simple to state and powerful in practice.

Buy at a large discount to a conservatively appraised net asset value. Make sure the enterprise is creditworthy. Favor companies that can grow net asset value over time and can convert resources through asset sales, spin offs, buybacks, and takeovers.

There are a few pillars you see over and over in Whitman’s writing and in Third Avenue’s philosophy.

The quality and quantity of resources on the balance sheet, the structure of the liabilities, and the true recoverable value of assets matter more than reported earnings. Whitman once said that earnings are very, very overrated as a metric. He was right. Accrual accounting can obscure the truth. A hard look at assets and liabilities tells you what the business is really worth and how much protection the balance sheet provides when times get tough.

Third Avenue favored buying securities at least 25% below readily ascertainable net asset value and looked for companies that could grow NAV at about 10% or more annually. The ideal investment is cheap on day one and can compound value on its own through retained earnings, smart reinvestment, portfolio reshuffles, or resource conversions. The Whitman lens is creditor math first. Does the company have the balance sheet to survive and improve. Can it meet obligations without heroics. Are maturities laddered. Is there covenant headroom. Can the company refinance without eating the equity. This is the part of deep value that saves you from cheap value traps. Cheap is not enough if creditors get paid and equity gets stranded.

Whitman was comfortable buying debt, post reorganization equity, preferreds, and common where the mispricing was greatest. That let him monetize value in bankruptcies and restructurings where the asset value and creditor rights were on his side.

The record speaks for itself. For almost two decades Whitman’s core approach outperformed broad benchmarks by a wide margin.

Distill Whitman to a single sentence and you get this. Buy well-financed, asset rich businesses at steep discounts to conservatively appraised NAV and insist on the ability to grow that NAV. That is deep value with a credit margin of safety.

Interlude. A modern framework that blends Graham’s simplicity with Whitman’s balance sheet discipline

Here is the playbook I like to run today. It uses Graham to tell you what to buy and Whitman to tell you which of those cheap names can actually survive and pay you.

Start with mechanical cheapness in the Graham spirit. Use rules that force you to pay far less than conservative value. Expect the basket to carry the load.

Liquidation value bargains. Price less than or equal to my rational Liquidation Value.

Price to assets.

Price to book less than or equal to 0.8 to 0.9, or less than or equal to 1.0 in markets awash in sub book names such as Japan, with haircuts for questionable assets.

Earnings or cash flow yield.

Enterprise value to EBIT less than or equal to 7 to 8. Free cash flow yield greater than or equal to 10 to 12 percent on normalized cash flow.

Income check.

Dividend yield greater than or equal to 6 to 7 percent only if it is covered by free cash flow and not masking leverage.

Do not overfit. Pull a wide net with two or three simple cuts. Then move straight to the balance sheet.

Impose a creditor’s test in the Whitman spirit. Cheap can stay cheap if it cannot survive.

Leverage.

Net debt to EBITDA generally less than or equal to 3.0 times for cyclicals and less than or equal to 2.0 times for secular no growth asset plays. For banks and insurers use capital ratios, reserve adequacy, and asset quality.

Coverage.

EBIT to interest greater than or equal to 3.0 times on mid cycle earnings. Stress test at minus one standard deviation.

Maturity wall.

No near term refinancing cliffs without clear liquidity. Ladder maturities. Maintain revolver availability and covenant headroom.

Asset quality and liquidity. Use realizable values, not accounting fantasies. Discount inventories, aged receivables, and specialized plant. Haircut non core real estate. Mark minority stakes realistically.

Working capital health.

Positive operating cash conversion, stable payables to receivables dynamics, and no chronic build ups that telegraph demand problems.

If the balance sheet fails the credit test, pass regardless of how cheap the multiples look.

Underwrite to conservatively appraised net asset value and the ability to grow it.

Estimate what a control owner could realize from the assets and what NAV looks like two to three years out with rational capital allocation. Favor businesses with visible resource conversions such as asset sales, spin offs, buybacks funded by free cash flow, take privates that already pencil at today’s price, or liability management that accretes to equity. The ideal setup gives a double engine. The discount to NAV closes while NAV itself compounds.

Demand alignment and control of the levers. Owner operators, large insider stakes, family or sponsor ownership with rational capital allocation, and explicit shareholder policies such as buyback authorizations tied to discounts and dividends linked to free cash flow raise the odds that value is realized. Avoid structures where creditors or unfriendly governance can strand your discount indefinitely.

Build the portfolio by the book. Embrace Graham’s group results. Hold about 25 to 40 names across sectors and geographies that pass the cheapness and credit filters. Keep initial positions around 2 to 4 percent. Scale toward 5 to 6 percent only when the balance sheet is ironclad and catalysts are live. Diversify by risk driver, not only by ticker. Combine asset heavy compounders such as real estate and royalties, classic industrials, special situations, and where you have expertise, a sleeve of distressed or post reorganization equities bought on creditor math.

Use time boxed, rules based exits. Install Graham’s sell discipline on day one. If price meets target value, often 50 to 100 percent from entry, or the discount to NAV closes ahead of plan, harvest. If 2 years pass without progress, recycle the capital unless the risk and reward have clearly improved, meaning a bigger discount, a stronger balance sheet, or new catalysts.

Use a hard stop if the credit story breaks. That means covenant breach risk rises, the maturity wall moves up without credible liquidity, or asset values prove illusory.

Treat risk as funding and liquidity first. Do not fund illiquid names with short fuse capital needs. Size down for micro caps and complex restructurings. Stress test to higher base rates and wider credit spreads. For international names, assume longer timelines and wider haircuts to asset marks. Hedge currency only if it materially alters thesis integrity.

Score it. Do not romanticize it. Keep a one page scorecard for each position. Include cheapness and which rule it passed, credit metrics like leverage, coverage, and the maturity map, asset and NAV haircuts and private market comps, catalysts and conversions with an expected timeline, and the downside defined as liquidation math and what can permanently impair capital. Revisit quarterly. If credit or catalysts weaken, act.

Execute with a steady cadence. Screen monthly. Refresh credit work quarterly. Re underwrite NAV annually or on material events. Rebalance systematically. Trim when discounts close. Add when spreads widen for non fundamental reasons. The edge is the process. Simple selection, rigorous balance sheet triage, and unemotional maintenance, not clairvoyance.

Put simply. Graham tells you what to buy. Very cheap, owned as a group. Whitman tells you which cheap names will survive and pay you.

Blend them and you get an asset anchored, credit aware, catalyst driven framework that scales in the U.S. and globally.

Section 3. Where the edge is now in small caps and deep value, United States and global

United States.

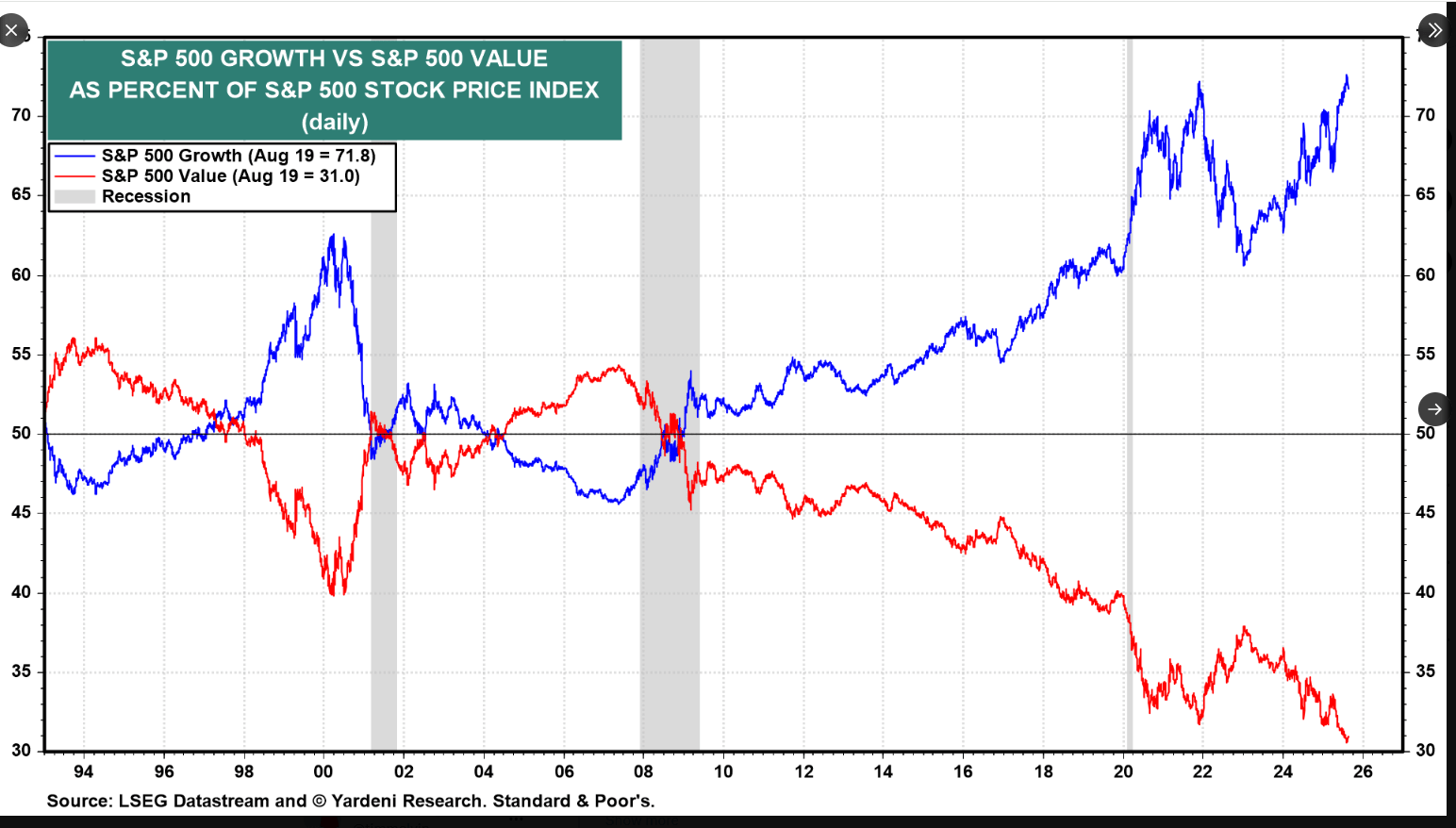

After a decade of mega cap dominance, small caps and deep value stand at unusually wide discounts to large caps. By late 2023, forward price to earnings gaps between the Russell 2000 and the S and P 500 had stretched to multi decade extremes. In 2025, small caps have rallied, including a roughly 7 percent August surge that pushed the Russell 2000 to new 2025 highs and within about 4 percent of its 2021 peak, yet small caps still trade at an average valuation discount of roughly 26 percent to the S and P 500. That is a lot of mean reversion potential if the economy avoids recession, inflation continues to ease, and financing conditions loosen. Smaller company earnings are more sensitive to domestic growth and to financing costs. As rate cut odds rise and refinancing risks abate, profit leverage improves. For the second quarter of 2025, Russell 2000 earnings growth was projected at roughly 69 percent year over year, with continued strength forecast. The policy backdrop since late August has been friendlier as the Federal Reserve acknowledged softening labor and opened the door to easing. This is the classic deep value setup. Low starting multiples, improving fundamentals, and a long runway for valuation spreads to compress.

The long view supports leaning in when spreads are this wide. Since 1927, U.S. small cap value has returned about 13.1% per year versus about 10.1% for the S&P 500. That 3 percentage point premium does not show up every year. It comes in cycles. The last decade was a drought. The 20 year trailing small value premium even slipped negative for the first time on record. Historically, that kind of washout has been a contrarian entry point that precedes robust catch up.

If the current discount merely narrows toward long term averages, the relative tailwind for small cap value could be substantial. Absolute returns can be boosted further by a cyclical upturn in profits.

How to express it in the U.S.

Combine Graham and Whitman. Use rules based baskets that own clearly cheap names, for example low price to earnings, low price to book, and positive free cash flow. Then apply a strict credit filter to screen out weak balance sheets and near term refinancing stress. You do not need perfect foresight. You need full value at a discount, group results, and issuers that can survive long enough to let value show up.

International.

Leadership is broadening beyond the United States in 2025. International equities have outpaced U.S. equities year to date by double-digit percentages and there has been a rotation toward value. Valuations abroad are lower on both price to earnings and price to book, which leaves more room for reratings if fundamentals continue to improve. Europe trades at meaningfully lower multiples than the U.S. and offers broad exposure to cyclicals and real assets.

A Graham and Whitman lens travels well in Europe. Emphasize balance sheet strength and discounts to tangible asset value in industrials and financials. Focus on disposals, balance sheet repair, and disciplined buyback programs as the resource conversions that close the gap between price and worth.

Japan is the poster child for price to asset bargains.

The Tokyo Stock Exchange has pushed reforms that target low return, low price to book companies. A very large share of the market still trades below book value. In recent surveys nearly half of Tokyo listed companies have traded below book.

The Japanese value index has hovered near 1.0 times book while the broader market sits closer to 1.4 times book. At the same time the macro picture has improved. Nominal growth around 3 to 4 percent and better governance have pushed returns on equity higher. When return on equity improves in a sustained way, value stocks rerate.

Japanese value stocks rallied sharply in 2023 and still have room to run because the raw material is plentiful. Sub book companies with improving capital allocation and rising profitability can move a long way as investors close the gap between market price and asset value.

Emerging markets also offer deep value, but the rules need to be stricter. You want bigger discounts, clearer governance, and hard asset backing or dollar cash generation. The payoff can be large when you find the right combination of price, assets, and credit strength, but the margin of safety must be larger because legal and liquidity risks are higher.

Appendix. Graham’s simple criteria, integrated and ready to use

I want this list in one place because it is the cleanest operating checklist for anyone who wants to practice deep value without turning research into performance art.

Why Graham leaned into simplicity.

The explosion of professional research made it hard to consistently win with complex analysis. The edge shifted to very simple price rules executed across baskets, with performance judged by group results.

Individuals have an advantage because they can search thousands of small and neglected names and should be able to find around 30 attractive issues at almost any time.

Rules for buying, selling, and allocating.

Investor, not speculator. Every purchase must be justified by impersonal reasoning that value exceeds price. Margin of safety sits at the entry price.

Pre set the sell discipline.

Two mechanical selection paths.

Buy below Rational Liquidation Value. Use a basket. Historically produced strong group returns for Graham, on the order of about 20 percent per year across roughly three decades when the opportunities were present.

One or two simple tests that prove full value is present. Price to tangible book value (P/TBV)(especially for banks and financials) and enterprise value ot earnings before Interest and taxes EV/EBIT) are mine.

A final reminder.

Screen first and analyze second. Start with mechanical filters such as Rational Liquidation Value, low price to earnings, high dividend yield, or low price to book. Weed out the obvious zeros. Favor stronger balance sheets and cash generation.

Buy a basket.

Expect a few duds, many singles, and a few home runs. Let the basket do the heavy lifting. Follow the sell rule.

Rebalance.

That is Graham’s simplicity with Whitman’s safety applied to a market that currently offers abundant raw material in U.S. small caps and in global price to asset bargains.

Why this matters right now

We have a rare alignment between philosophy and opportunity.

Graham’s data driven minimalism says buy groups of very cheap stocks and let the group carry you.

Whitman’s credit first discipline says make sure the companies are strong enough to survive long enough to pay you.

The facts on the ground look favorable. The small cap discount in the United States remains historically wide even after a strong rally. Earnings leverage is improving as financing pressures ease. Abroad, value leadership is broadening with Europe at lower multiples and Japan full of sub book companies facing constructive governance pressure. For patient investors who stick to a process that is simple, repeatable, and credit aware, the next few years should be fertile for deep value done right.

That is the whole point. Buy full value at a discount. Marry simple selection with rigorous balance sheet work. Let group results compound. Trim into strength. Recycle when the clock runs out. This is how you control what you can control and stack the probabilities in your favor, in the United States and around the world.

Tim Melvin

Editor, Tim Melvin’s Flagship Report